HR leaders are continuing to see the function fundamentally shifting, especially with the meteoric rise of AI. One such way is away from siloed, credential-based talent strategy—from traditional hiring to strict job responsibilities and roles—to a more fluid skills-based strategy.

“Simply implementing a skills taxonomy or talent marketplace may not be enough to achieve target outcomes without the change management to align cultural norms, career architectures, performance management systems and the like,” says Craig Friedman, senior talent strategist at St. Charles Consulting Group. “Creating a culture of continuous learning needs a culture that makes time and space for it.”

Friedman spoke with StrategicCHRO360 about exactly how HR leaders can make the shift to a skills-based strategy, common pitfalls to avoid and how technology teams can help.

What are some of the biggest mistakes companies make when trying to shift from traditional role-based models to skills-based approaches?

Many companies over-engineer skills taxonomies on their first attempt, to the point where they have hundreds of thousands or more unique skill definitions to administer and maintain. Such complexity can collapse under its own weight, being impractically large to be effective.

Other firms take an overly abstract view of skills, seeking to map the collective knowledge of the enterprise without tying skills to practical concerns like work tasks and job responsibilities, which help scope and streamline efforts.

Finally, some companies start their skills journey with a localized pilot, without a governance framework that aligns with the broader organization. Such efforts can optimize skill frameworks and structures for the pilot group, but without the ability to scale to the needs of other groups and talent systems.

The easiest methods to assess skills are often the least reliable: self-reporting and computer inference. Many companies find the need to validate skills with more advanced, but more cumbersome, methods like objective assessment, demonstrated capability or peer and manager attestation.

Whatever the methods used, each company will eventually need to arrange a system of coordinated methods to validate skill attainment objectively and equitably. Also, the work doesn’t end once a skill is validated. Skills atrophy over time, and skill profiles need incentives and systems to be kept continually current.

Simply implementing a skills taxonomy or talent marketplace may not be enough to achieve target outcomes without the change management to align cultural norms, career architectures, performance management systems and the like. Creating a culture of continuous learning needs a culture that makes time and space for it.

Creating just-in-time, skills-based learning solutions requires a curriculum infrastructure organized around skills, not career or organizational assumptions. Talent marketplaces need infrastructure and policies to promote usage, define parameters, validate skills and support resource sharing. Skills-based recruiting needs support to remove implicit bias, expand onboarding practices and implement new skill assessments that replace college degrees.

There’s a perception that moving to a skills-based model requires a massive overhaul. Can this shift be done incrementally, and if so, how?

Absolutely. Skills-based talent is not just a single strategy but a collection of talent strategies that revolve around a common theme. They leverage skills data to maximize the efficiency and adaptability of talent practices. As such, skills-based transformations are fundamentally data-driven business transformations. This is helpful because much is known about conducting data-driven transformations from other business areas.

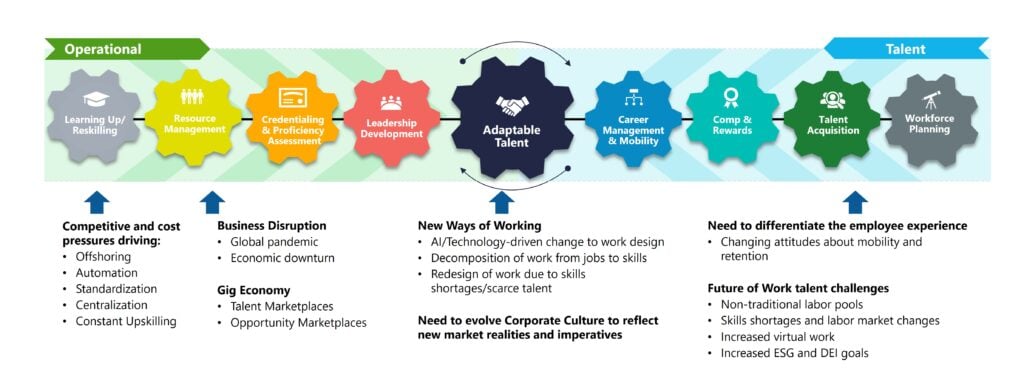

There is no single correct way to go about a skills journey. Skills data is strategically linked to several areas of one’s business. Skills are linked to people, jobs, work tasks and workforce planning.

Skills plus people link to employee profiles, skill assessments and L&D programs. Skills plus jobs links to job architecture, organizational design, career mobility and leader development. Skills plus work tasks links to resource management, work design and talent marketplaces. Skills plus workforce planning links to recruiting, compensation and business capability.

A skills-based talent journey starts with one’s business drivers and tends to proceed from that point up or down the talent value chain.

If one is redesigning one’s work tasks due to AI-enabled or talent-scarce environments, one will probably start one’s journey with skills-based work design. If they use a talent marketplace to manage business disruption or improve staffing efficiency, they will probably begin with skills-based resource management.

If they face recruitment challenges and labor market shortages, they will probably start with skills-based recruitment. If they need to develop new business capabilities to enter or quickly capture a new market opportunity, they will probably start with skills-based workforce planning. They may begin with skills-based job design if they need to update their job architecture, standardize job requirements or map similar job descriptions due to a recent merger.

However, not all journeys will result in complete transformations—some will remain localized to one area of the talent value chain. Not all journeys will proceed across the entire enterprise—some will remain targeted at particular business lines or divisions where they are needed most.

Not all journeys will proceed to the most advanced maturity level—some will remain pragmatic and value-added. There is nothing wrong with employing skills-based talent solutions that are localized, pragmatic and limited and still achieve real business value.

Any of these is a fine place to start. Each starting point has its pros and cons, benefits and challenges. In fact, many companies pursue several of these journeys simultaneously in various parts of their organization. And that is fine, too.

It just takes a bit of governance and coordination to ensure that when these separate efforts develop, they do so with a common language and set of guardrails so they can ultimately share skills information across the enterprise.

How can HR, learning and technology teams better collaborate when building a skills-based system, especially in large, complex organizations?

Establishing a governance framework is critical to long-term enterprise skills journeys. As highlighted above, skills frameworks need alignment across business lines and across the talent value chain. Skills journeys also need coordinated change management to align systems and promote adoption. In very large organizations, organizations may need to federate governance.

It may make sense to split skills frameworks and governance across business lines in vastly diversified organizations. In global organizations, consideration of regional and jurisdictional differences may come into play, as can aligning with the practical realities of international or regional technology ecosystems.

Finally, skills themselves can be federated. The dynamics of rapidly changing and specific technology skills can differ significantly from deep functional or regulated technical skills in engineering, law or medicine.

By the same logic, both those skill domains can vary dramatically from shared, enduring business and leadership—so-called “soft skills.” Depending on one’s business, some organizations may choose to federate the governance, implementation and maintenance of such skills so as not to burden other vastly different groups with the practical necessities of their own.

Still, even in federated skills governance regimes, the enterprise must develop mechanisms for data interface and harmonization to support common reporting and cross-enterprise transparency. Skills-based governance should be thoughtfully created in a way that engages representation across all affected talent functions, technology groups, business lines and meaningful regional differences.

While they all won’t participate equally in every pilot or phase, establishing transparent lines of communication will help them develop strategies to provide depth when and where needed, and alignment as appropriate.